Schubert’s Impromptus Opus 90 – Fantasy for Large Orchestra

Written by Franz Schubert, Arranged by John M. Davis

When I first played on the piano Schubert’s Impromptus Opus 90 #1, it struck me as very cinematic. It was written in 1827, long before movies were invented, but it told me a story of soldiers marching into a city, being greeted with fanfare and hospitality, attending a dance with the local ladies then departing to a brighter horizon. I see the Meryton militia in “Pride and Prejudice” (1813) attending the ball at Netherfield. The Romantic world of Jane Austen is supremely cinematic, as evidenced by the many adaptations, but the Romantic world of Schubert is equally that and modernist as well. His marching band might be conjured in a symphony of Charles Ives, and the dichotomies that obsessed Schubert — major and minor, triplets and two’s, chaos and quiet — are just as relevant in the 21st century.

Modest Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at and Exhibition” (1874) is equally programmatic, and is, like the Impromptus, a piano composition. It is best known today in Ravel’s techinicolor orchestration, but I discovered that there are at least twenty-six other arrangements. There must be a few versions of the Schubert. I found none. How could this be? Have others not heard in it the same Cinemascope epic that I heard? Should I adapt it myself, because if I don’t then perhaps no one will?

I’ve always orchestrated for practical ensembles, but this time I figured I could arrange for an all-star group of musicians — specifically the New York Philharmonic. I’ve been a season ticket holder for over twenty years, and I know exactly the effects of theirs that I like the most. The terms “Impromptus” and “Fantasia” are very similar, both deriving from improvisation, and I figured if I was writing for the New York Philharmonic then I was definitely writing a Fantasy. Thus I started this “Fantasy for Large Orchestra.”

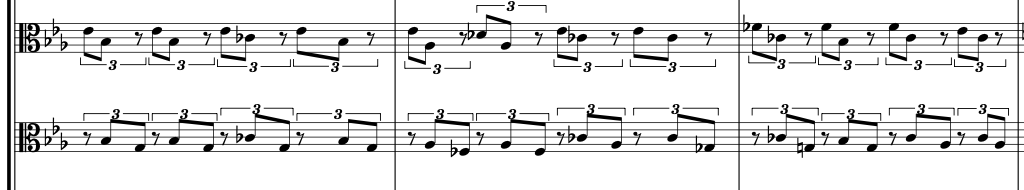

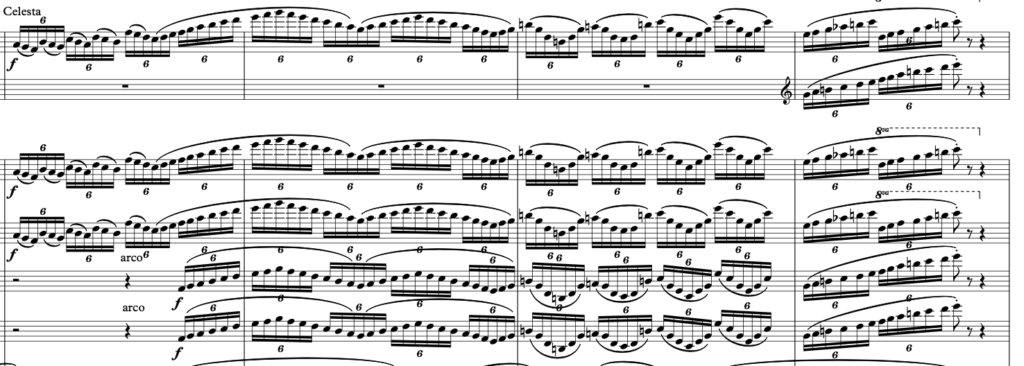

In Ralph Vaughan-Wiliams “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” he splits the string section into two orchestras plus a string quartet. I thought I could do something similar, so I divided each string section into A and B groups which are seated opposite each other. The many triplets in the left hand might become dull if reproduced literally, so I split the triplets into groups of two that bounce back and forth from left to right sides of the stage.

I did a similar thing with the vibraphone part – two alternating hands playing triplets. I could also use the two sections like a delay, so if Viola A has a pizzicato note then Viola B could repeat it an eight note later. When I wanted a large chord up and down the string section the A and B orchestras made it easier to notate without messy divisi.

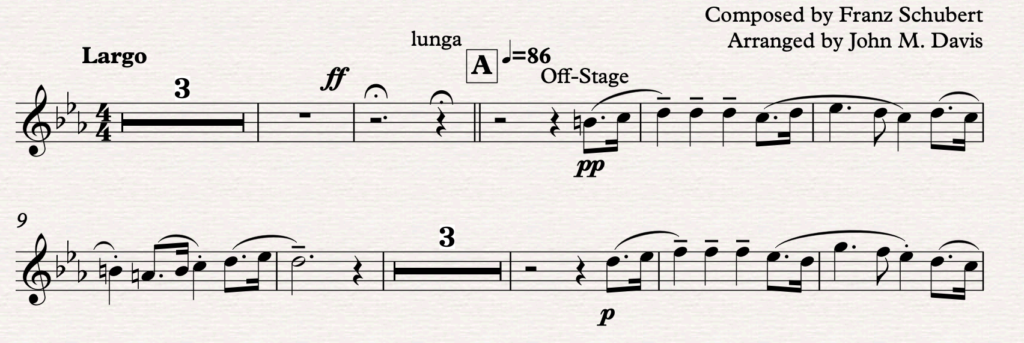

I enjoy concerts when the leaders of the sections have solos, so I strove to give every first chair their moment in the sun. To maximize the colors I expanded the instrumentation to include a soprano saxophone (in a nod to the sax in Ravel’s “Pictures”), English horn (my old instrument), Eb clarinet, tuba solo, viola solo, piccolo solo, etc. I even have an off-stage cornet, which is my homage to the off-stage choir in Holst’s “Neptune.” I’ve enjoyed many pieces in Geffen Hall that take advantage of the sonic effects of players off-stage, in the back of hall or in the balconies.

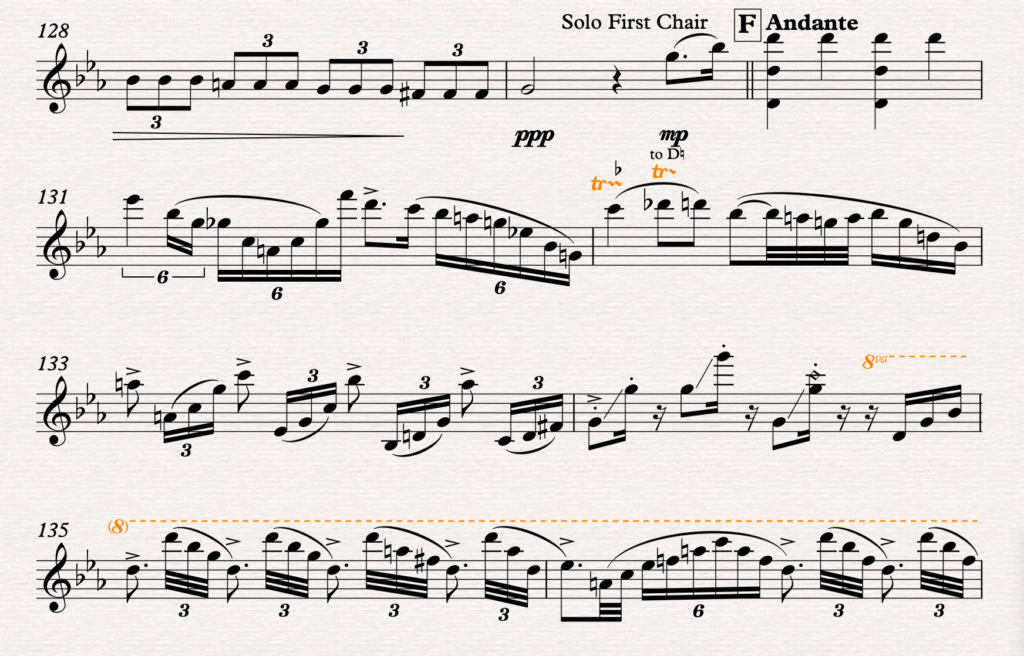

The editor of the piano version offers in a footnote that the middle section (the Netherfield ball) should be played like a singer over a pizzicato cello bass line with a delicate accompaniment in the middle. I cast my singer as Fritz Kreisler playing a virtuoso violin solo, and the delicate accompaniment becomes a magical music box. It’s my favorite part of the piece.

In the quest for big screen excitement I added runs and glissandi straight out of John Williams’ Harry Potter scores. The simple G octaves of the piano introduction become a nod to Williams’ misterioso overture to “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” I was a little wary of adding too many notes that aren’t in the original, but I did add a few counter-melodies to impart a cinematic sweep beyond what two hands could perform.

Rimsky-Korsakov, another inspiration, is invoked in the first bar of the above-mentioned violin solo, so when the piece transforms subtly and inevitably from C minor into C major I give the celli the wide “Scheherazade” triplets like a rocking ocean ship.

After one more fit of bombast and runs, the music quiets and the soldiers depart. The cello solo offers some regrets to friends newly made, but the simple repeated chorales in the brass, then the winds, then the strings offers the most satisfying of C major conclusions — a happy “The End” superimposed over a sunset.

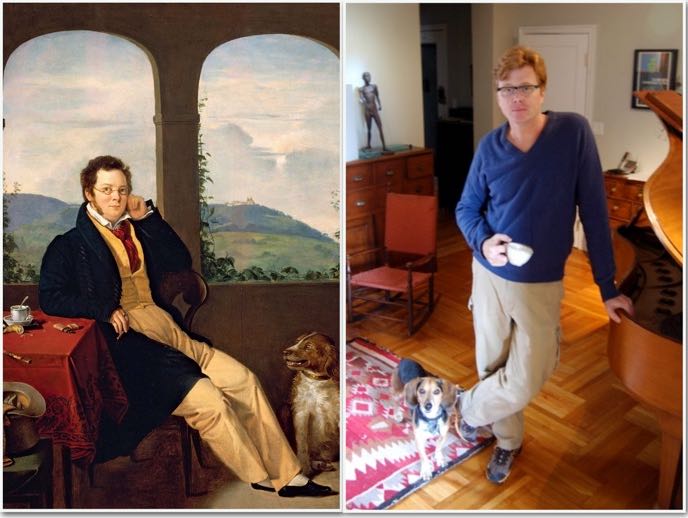

Franz Schubert might have hated this, but the many versions of “Pictures at an Exhibition” all came after Mussorgsky’s death and without his input. Schubert died very young at thirty-one. He was a genius, and I am a journeyman. If time and talent didn’t so separate us perhaps we could have gotten along, or perhaps we would have appreciated some of the same music. Or liked the same movies. Schubert was a song writer, and songs are meant to be performed. Hopefully this version of one of his piano improvisations makes for a good show.